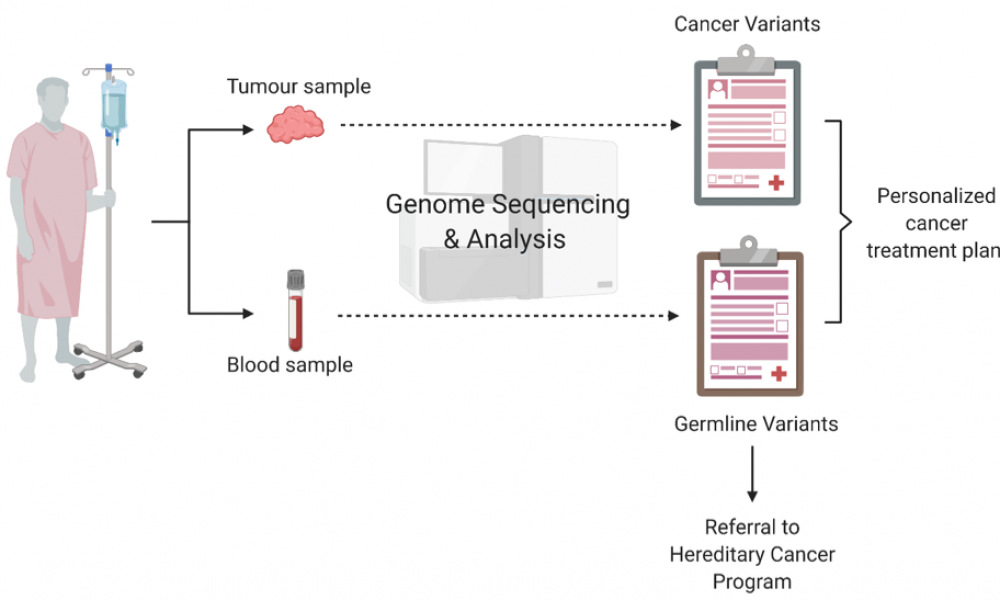

Cancer is a disease of the genome. Using data from next-generation DNA sequencing technology, genome scientists and oncologists can work together to better inform an approach to individual patient treatment planning that is more targeted and personalized than ever before. But, in the process, they can also uncover information about a patient, such as their family’s susceptibility to hereditary forms of cancer and other diseases.

What should scientists and clinicians do with all of this information? What’s the best approach to managing these findings? A new clinical framework attempts to address this increasingly common conundrum.

Personalized OncoGenomics (POG)

Every patient carries genes inherited from their parents. Individual variation in this inherited genome—known as germline variants—can influence an individual’s predisposition for developing cancer and other diseases and can be passed on to future generations. Research has shown that germline variants in cancer predisposition genes underlie five to 10 per cent of all cancers. In addition to susceptibility, germline variants may influence the way a tumour developed, or a patient’s immune response to cancer and their response to treatment.

BC Cancer’s Personalized OncoGenomics (POG) program is a precision oncology initiative that performs whole genome and transcriptome sequencing to identify targetable genetic alterations in patients with metastatic disease. The program has enrolled more than 1,100 patients to date; 83 per cent of cases have yielded actionable findings. Closely interfacing with the Hereditary Cancer Program (HCP) at BC Cancer, POG is uniquely positioned to establish best practices for identifying and reporting germline variants of potential clinical significance.

The framework

In a paper published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, Cancer Spectrum the POG team proposed a framework, based on eight years of experience using whole genome and transcriptome sequencing to influence patient care, for the identification, evaluation and reporting of germline variants that may have implications for the health of cancer patients and their families.

“This paper outlines our extensive clinical research experience with the use of whole genome and transcriptome sequencing of the tumour and germline in a publicly funded healthcare system,” says Dr. Kasmintan Schrader, Scientist and Staff Physician at BC Cancer and senior author on the study. “By documenting our experience, we hope to motivate those working in programs similar to POG to consider some of the same issues that we did.”

The framework relies on the concerted efforts of the POG Ethics and Germline Working Group, a multi-disciplinary team consisting of oncologists, medical and molecular geneticists, pathologists, bioinformaticians and other scientists, an ethicist and lawyers.

“The Ethics and Germline Group is important because it brings together different perspectives to make an informed decision that is best for the patient,” says Katherine (Katie) Dixon, a graduate student working in Dr. Schrader’s group and first author on the study.

A key aspect of the published framework is the universal reporting of cancer-related, clinically actionable germline findings as a part of participation in the study and as outlined in the informed consent. These results are returned to the patient by their oncologist, and a referral is made for genetic counselling through the HCP.

For germline variants unrelated to cancer, the POG program has adopted an opt-in procedure.

Patients are made aware that germline findings may not directly impact their individual cancer risk, prognosis or treatment, including variants that may have implications for cancer screening and risk reduction for family members carrying the same inherited germline variants. Of the patients enrolled in the POG program, between 2012 and July 2019, 97.9 per cent opted for the return of germline findings, including clinically actionable information regarding other genetic diseases, unrelated to cancer.

“This number shows that patients do highly value genetic information and are willing to receive it,” says Dixon. “Even though it may not benefit them directly, patients have a lot of concern not only for themselves but also for their families.”

The established framework for the return of clinically relevant germline variation to patients enrolled in POG is consistent with the overall goal of the program: to characterize the complete genomic architecture of an individual cancer by making evidence-based interpretations and decisions about actionable findings, maintaining data transparency and allowing opportunities for clinical translation.

“This paper highlights the importance of identifying cancer susceptibility findings as well as germline variation that goes beyond that,” says Dr. Schrader. “There is well-supported clinical utility in understanding if a patient or family is (or is not) at an increased risk for cancer with regard to cancer screening recommendations and the potential for cancer risk-reducing strategies. If identification of cancer susceptibility was more widespread, we could decrease the incidence of certain cancers in the population. Additionally, further understanding of inherited factors that may contribute to the way a tumour evolves or the way the body may behave in response to treatment will be important as we continue to truly personalize cancer care.”